Nuclear fusion is a relatively safe and almost unlimited form of carbon-free power. It generates energy inside stars; it is how the sun gives us light and heat, and it may well be the source of the world’s energy in the near future.

On 5 December 2022, while many were transfixed by Prince Harry’s Netflix trailer or by the Brazil v Japan World Cup football match, researchers at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in California focussed a laser of 2.05 megajoules onto a tiny capsule of fusion fuel and sparked an explosion that produced 3.15 megajoules of energy.

In other words, more energy came out than had gone in.

Fusion holds the enticing promise of nuclear energy without the terrifying radioactivity of nuclear fission-driven power. However, it is not as close as the 5 December breakthrough might suggest. It requires temperatures of millions of degrees – hotter than the sun – to cause hydrogen ions to fuse into helium in order to release useful energy, and this is extremely difficult to achieve. At least the NIF result shows it is possible.

With any new technology, and any new energy source, comes a raft of new political, scientific, cultural, economic, commercial, ethical and legal considerations. In this article, not being qualified to discuss the others, we’ll take a look at the legal.

The UK government, like the EU, is already building the framework for regulating future fusion energy facilities. It acknowledges that the hazard and complexity will be greater than current research centres, but has concluded that, because the radiological hazards associated with fusion technology are much lower than those for fission reactors, the UK will not incorporate fusion energy into existing nuclear regulations, because those regulations all relate to nuclear fission.

The government will therefore use the Energy Security Bill to remove uncertainty in the current legal framework, and then regulate fusion with new regulations. If this is the right approach, then developers will prefer the UK to any jurisdiction that tries to regulate fusion in the same way as it is currently. If it is wrong, then an overly lax regulatory environment will result in the British population suffering a fiery and exciting annihilation.

A year before the 5 December breakthrough, the government published its Green Paper on regulatory framework for fusion energy in the UK. It dealt with the three issues of safety, transparency, and innovation, aiming to ensure that the public are kept safe and informed while also trying to badge the UK as the place to develop fusion energy. The results were published in a report on June 22.

The US and the EU

In the United States, there are already several companies, including Google and Helion Energy, hoping to profit from fusion technology in the next decade, and so, as with the UK, a clear regulatory framework needs to be created.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) recommends regulating fusion under a by-product materials framework rather than using the existing nuclear regime. Again, this makes a clear distinction between fusion and fission, recognising that the current regulatory regime unhelpfully uses the word “nuclear” as shorthand for nuclear fission.

The European Union has also been exploring its regulatory approach to nuclear fusion. Its task is in some ways harder than either the UK’s or the USA’s because its member states have in many cases already begun pondering their own approach to balancing opportunity against safety. Its white paper on the subject was published in June 2021 and has a strong focus on the handling of radioactive waste, without the commercial call-to-arms present in the UK’s approach.

Intellectual property and China

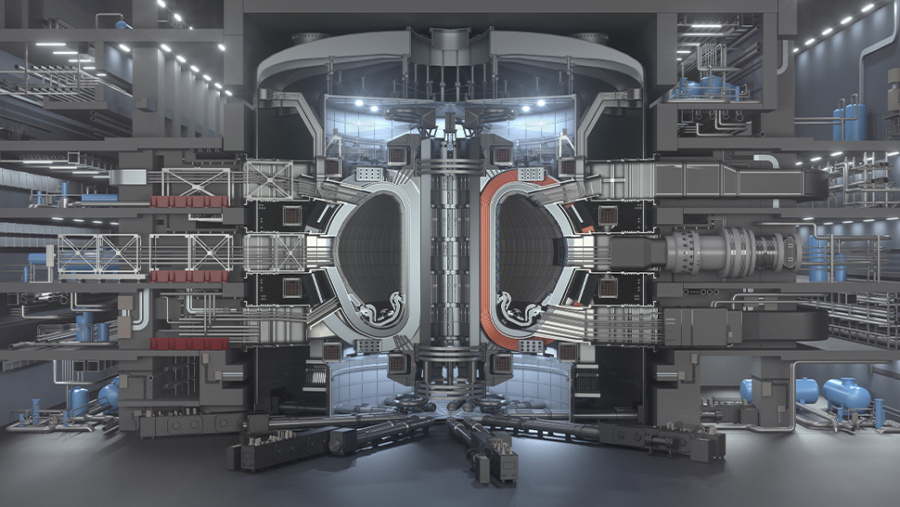

This brings us to another important legal issue, intellectual property rights, and to another important country: China, which has been no slouch in fusion research. Twenty years ago, it teamed up with the US in the International Thermonuclear Energy Reactor (ITER). It is still a member of ITER, which is a larger and more lavishly funded rival of the NIF – and now includes both the EU and the UK. China also conducts its own fusion research – for example creating an “artificial sun” that burned for seventeen minutes last year.

China came first in a nuclear fusion patent ranking compiled by the Japanese research company astamuse, with the US, UK and Japan coming second, third and fourth respectively. Remarkably it was a British company, Tokamak Energy, that came first in the corporate ranking, having in 2022 became the first private company to achieve a plasma temperature of 100m degrees.

Intellectual property law and, more generally, the law of confidentiality, is of course the legal approach to the commercial problem of protecting intellectual creations, know-how and trade secrets. Yet moving beyond that is the question of state secrets. Some nation states make use of state secrecy laws, which typically carry more severe sentences for breach. It is to be hoped that the world will continue to take the collaborative approach to fusion energy research typified by ITER, but it is likely that individual countries, like individual companies, will fiercely defend their technology in the near future.

China has already included fusion research as a category in state secrets protection. Yet overall the message is positive: we do seem to be a step closer to carbon-free energy generation in a well-regulated legal environment.